So the film Free Willy is 30 years old (that is 1993 by the way..). I’m fairly sure that for many of us, the story about how this iconic orca found some degree of freedom eventually, will have been the origin of our passion about whales and dolphins. In 1979 he was taken aged two from the icy waters around Iceland, moved to an aquarium in Mexico City and made to endure a daily routine performing tricks for tourists.

Keiko’s story is one of hope and determination, but ultimately doesn’t have the fairytale happy-ending that everyone will have hoped for. However we mustn’t forget that this captive whale is still the only killer whale held in captivity that, so far, has been released into the wild. Some might argue that Hvaldimir, the Beluga defector from Putin’s secret cetacean spy programme (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/29/suspected-russia-trained-spy-whale-reappears-off-swedens-coast) is another, but he’s more an escapee than a released prisoner.

If we wind the clock back to 1996, I was working for IFAW over in the U.S, having completed my post-grad research into stereotypic behaviour of bottlenose dolphins in captivity in Belgium. Through a series of chance connections, I was invited to join up with the team that were preparing to move Keiko to Iceland. The very practical logistics of doing this were immense, and there was an inevitable focus on just making this all happen. But monitoring what the extraordinary and life-changing impacts were going to have on Keiko’s behaviour was also important. And I suppose that's where I came in.

There was so much to learn and observe and study – moving Keiko from a captive environment in a Mexico City aquarium to a vast sea pen in icy Arctic waters via a two-year rehab exercise in a tank at Oregon Coast Aquarium would be a culture shock to any sentient being – For Keiko, this is was going to be a transformational, but also potentially stressful.

I first met Keiko when he was in the holding pool in Oregon.

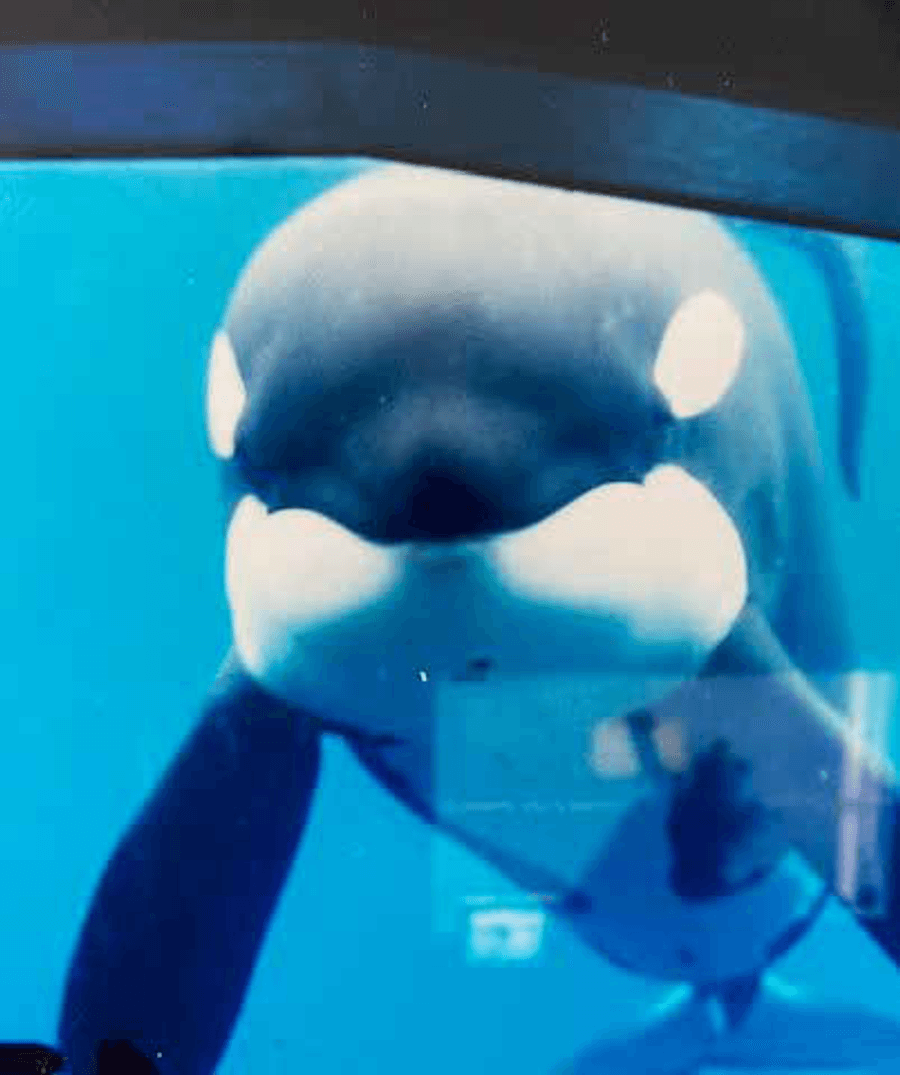

The photo here is unpublished and shows Keiko looking at us through the underwater window. His time at Oregon was the start of introducing him to colder seawater, and allowing him the freedom to express a degree of natural behaviour that he hadn’t experienced since he was two years old. I have to admit that there was a sense of hope more than expectation around his rehabilitation. Keiko absolutely loved human beings.

In 1998, I was at the release pen in Iceland’s Klettsvik Bay as Keiko was gently lowered into the sea. It was the first time in nearly twenty years he had experienced anything approaching freedom. To just be there, given all the hype and publicity and genuine outpouring of humanity that had resulted in that moment, was utterly extraordinary. On several subsequent study visits, I recorded his behaviours – fast swimming, resting, play, possibly due to the simple joy of being able to express natural activity that would have been just a distant memory. But it was clear that he still had a strong connection and bond with humans - sad as that was, I guess it’s not to be unexpected, after all he had to spend almost his entire life with humans.

We assume of course that animals held in captivity against their will always flourish on being set free. But that’s an inevitable human assumption. Setting Keiko free was the objective and the imperative and followed massive public pressure, but it had never been done with an orca before. It wasn’t as if there was a tried and tested roadmap that everyone could follow, however genuine and heartfelt their intentions. What struck me most was the intertwined dependence and affinity Keiko had for humans. He had no reason to separate the two even though we can see that both are different.

The reason this is all so topical is because of the very strong likelihood that we’ll see more attempts to release captive cetaceans back into the wild over the coming years. Aquariums will be closing down for a multitude of reasons (but mainly because of a moral rejection amongst tourists around their place in the 21st century) and so we need to prepare for what that means. For a start there needs to be a much greater understanding of how cetaceans react to the freedoms that they are presented with, and aside from Keiko and a handful of other projects, there’s nothing to model what that looks like. Hope and faith alone can’t suffice. This is why projects like the Beluga Whale Sanctuary are so important to keep pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved, with the ultimate aspiration of setting all captive cetaceans free.

Sally Hamilton, CEO, ORCA