It's perhaps no surprise that our blogs tend to focus on what is happening to cetaceans in our oceans, since that is where nearly all of ORCA’s work takes place. But, there are six distinct species of freshwater cetaceans globally, with the Indus river dolphin in Pakistan only being formally recognised in 2021.

Alongside the Ganges river dolphin found in neighbouring India, the Indus river dolphins are the only surviving members of a superfamily of cetaceans called Plantanista which lived in the prehistoric Tethys Sea.

One theory is that as the sea receded and the sub-continents formed, the Plantanista adapted to live in the rivers fed by water from high Asian mountains, including the Himalayas. But in Asia, rivers are a crucial resource for multiple reasons - for transport, food, water and irrigation.

The Indus river dolphin has existed rather uncomfortably alongside its human neighbours for centuries, competing for fish and with a diminishing range in proportion to an ever increasing human population. While at one point, they had the freedom to inhabit a 2,100 mile stretch of the main river, as well as 5 tributary rivers, they are now restricted to 428 miles of the lower Indus. The largest pod, of nearly 1,000 individuals, are squeezed into a mere 90 mile stretch of the river between two barrages.

As if this all didn’t sound sufficiently bleak and dreadful, then consider the fact that the Indus is one of the world’s most polluted rivers and also that water abstraction for irrigating crop fields is ever-increasing, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that there wasn't much hope for the Indus river dolphin.

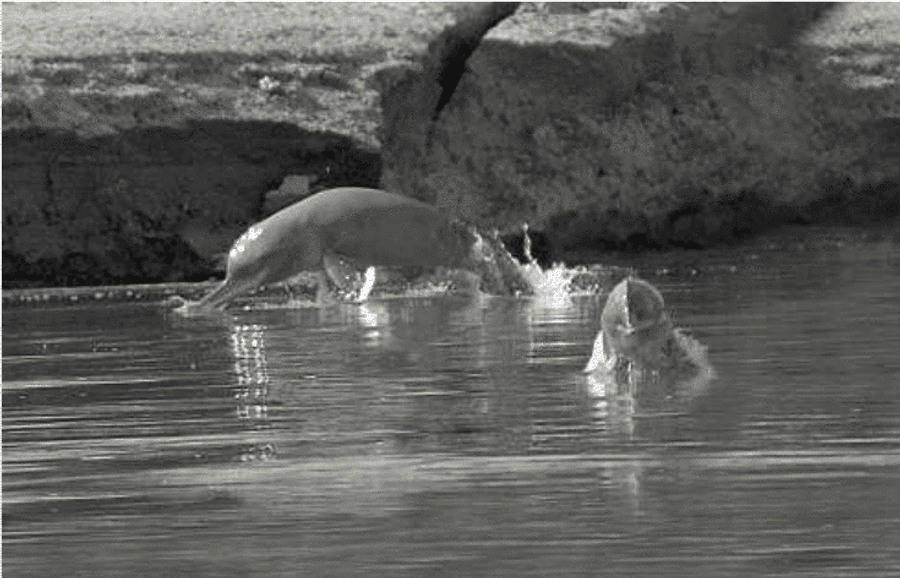

So it was a wonderful surprise to find that back in 1974, when there were only around 150 dolphins living in the Indus, now there are nearly 2,000. Even more surprising, and reassuring, is that in a very real “poacher-turned-gamekeeper” scenario, the fishing community along the Indus have turned into passionate and active citizen scientists and are leading the effort to safeguard the population.

In a pioneering project run by WWF, the fishing community have been recruited as eyes and ears, and their incentivised efforts to safeguard and monitor the dolphin population have in turn changed mindsets. A river that is healthy has dolphins in it, but an unhealthy river has no dolphins because there are no fish. This has resulted in a quiet transformation of local opinion about the dolphins, and instead of a perception that they are the enemy, in an ongoing fishing competition, an acceptance of co-existence has been struck. Even though the fishing community recognise that protecting the dolphins gives them less time and opportunity to catch fish themselves, they are content with the balance that has been struck.

WWF have incentivized the local farmers and fisherfolk to report dolphin sightings, especially of stranded dolphins who get stuck in the irrigation channels that branch out for miles out of the Indus river. Some get a small cash sum if they use their boats to reach the area. Others are celebrated on social media, which can encourage others to call in dolphin sightings and help on rescues. Wildlife officers (some of whom are the descendants of a river-dwelling community of dolphin hunters) act as first responders to rescue the stranded dolphins. They also provide help to researchers in the form of boats for surveys and their experience.

“We are not greedy. We are not employees at WWF. We protect the dolphin because it is a creature of God.” said one fisherman.

A balance like this is fragile and needs to be propped up, managed and maintained. Its precedents lie the community projects that have also achieved a balance in managing the conflict that exists when living alongside lions and tigers and elephants. Once again it’s the concept of citizen science in action - engaging with individuals, securing their buy-in and making them a part of the solution rather than imposing schemes and projects that do not respect their expertise and insight.

The Indus river dolphin’s future can only be secure if it is seen and recognised as something worth saving by the communities who depend on the river for their livelihoods. Khatoon, an Indus fisherwoman said; “We feel happy when we protect them, Dolphins are our friends. We care about the dolphins.”

ORCA's work to protect whales and dolphins has never been more important and to help safeguard these amazing animals for the future we need your help. Please support our work by donating at www.orca.org.uk/donate to help us create ocean's alive with whales and dolphins