Welcoming Ocean Conservationist Nina on board the DFDS King Seaways!

Hello everyone! I’m Nina, an Ocean Conservationist for ORCA, and I am currently Mathilde’s counterpart, rotating every two weeks on the DFDS King Seaways throughout the summer season, sailing across the North Sea from Newcastle, UK, to Ijmuiden, Netherlands. I’ve finished my first rotation and have been lucky enough to spot some playful bottlenose dolphins heading northbound to Newcastle on a number of my crossings, as well as some shy harbour porpoises bobbing around near the bow of the ship. Eager guests and I on board the King have also spotted gannets, guillemots, kittiwakes, northern fulmars, and black-backed gulls along the way. By the end of the season, I am hoping to spot some Atlantic puffins, but they are proving to be a little bit elusive at the moment. Fingers crossed I spot some as the season continues!

Over the past two weeks, I have sailed into Ijmuiden several times, and each time have been struck by the scale of the wind farms that border the entrance to the Netherlands. As Mathilde said in her blog, wind farms have both positive and negative effects on marine wildlife. On the one hand, they create noise pollution, particularly during the construction phase, which can interfere with whale and dolphin communication and navigation. On the other hand, once implemented, they can provide habitats for a variety of organisms and sustain the marine food web. Sailing past these wind farms every other day got me thinking about a phenomenon called biomimicry, a concept that draws on nature, natural structures, and processes that I thought I would share with you. It is derived from the Greek words bios (life) and mī́mēsis (imitation), which means ‘imitation of life’. Janine Benyus, author of ‘Biomimicry: Inspired by Nature’ coined the term in 2002.

“When we look at what is truly sustainable, the only real model that has worked over long periods of time is the natural world” – Janine Benyus

Essentially, biomimicry is a concept that has the potential to solve human design challenges by copying nature. It is not always necessary to create a new solution to an existing problem; sometimes, you can adapt and improve existing solutions. After all, the animal kingdom is the best historical living record of evolutionary trial and error that we can learn from.

The Humpback Whale

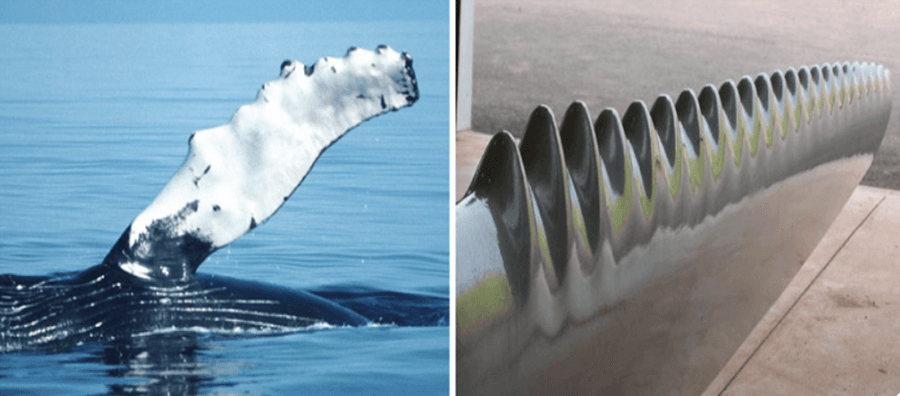

On this route through the North Sea, we are lucky enough to occasionally see humpback whales - although they are rare in this area. The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) has long been considered a favourite of our ocean giants for a number of reasons. Humpback whales are one of the most acrobatic of baleen whales, typically launching themselves out of the water, fins raised, and slapping back down at great speed - a spectacle to behold! And yet some of you may be thinking, how can whales that size breach out of the water so effortlessly? Well, it is actually predominantly to do with their pectoral fins. Humpback whales have the largest pectoral fins of any cetacean, which can reach up to 7m, around one-third the length of its body. The leading edge of their fins are covered in what is known as tubercles, which are small rounded bumps situated along the edges of their fins. Humpbacks have evolved to have these tubercles on their fins, meaning they can swim underwater efficiently and manoeuvre (relatively) quickly, a tactic designed to help them feed on prey more effectively. This adaptation, in particular, is vital in the current climate, as commercial shipping and trade rises globally, increasing the risk of ship strike where high-density humpback whale highways are distributed. Part of our role as Ocean Conservationists is to raise awareness about ship strikes and other threats to cetaceans, not only to the guests we meet but also with the crew onboard our partnering vessels.

The tubercles on the pectoral fins of humpback whales act as passive-flow controls and reduce drag underwater whilst manoeuvring. Humpbacks are thought to be the only cetaceans utilising the tubercle effect in order to increase their hydrodynamic performance. They are setting an example through biomimicry that can be adopted to solve human design challenges. Humpback-inspired wind turbines have the potential to reduce maintenance of offshore wind farms due to their efficiency, and in turn, reduce additional noise pollution in the surrounding marine environment. They also produce electricity more efficiently, reducing waste products and promoting a greener way to produce energy. Although the tubercle effect is not a new concept, it still requires additional research and understanding.

Nature is our best teacher. Concepts such as the tubercle effect, derived from the physiology of humpback whales, and other examples provide future insight and much-needed education surrounding cetaceans and the role they play in our ocean environment. Their anatomy serves as a model for effective technology that has the potential to pave the way toward a greener (and bluer!) planet. These ocean giants play a crucial active role in regulating our Earth’s climate, both physically and artistically, and require the utmost protection worldwide. ORCA strives to see oceans alive with these wonderful creatures and creating awareness about their important role in the ocean environment is one step closer to safeguarding the future of cetaceans and their habitats.

Check back in with me in the next couple of weeks and see what I get up to across the North Sea. Hopefully, I will have more marine wildlife sightings to share with you all!

Ocean Conservationist Nina (North Sea)